By Darren Proulx

This essay examines Montreal, QC and how the city has successfully created public space where people want to spend their evenings, weekends, and free time.

Many people will argue that Montreal is a winter city and the few short months when it is sunny and warm force people to come out of their homes and spend time outdoors before the next snowstorm…This however, would fail to recognize the many successes the city has achieved in planning and designing public spaces within the context of the city.

This essay could be spent summarizing the ambience and design of Parc Laurier, Parc La Fontaine, the Lachine Canal, or the Canadian Centre of Architecture as excellent public spaces..but when the whole city is considered a few different reasons come to mind. I will pick up on a Globe & Mail Article about how Montreal is building a city for people

A description of Montreal’s efforts is shared below.

- Housing & design that promotes interaction

The Rowhouses in Montreal can be characterized as “Dense and Low-Rise,” with 3-4 stories typically and set-back little from the street with front doors opening to the sidewalk. The density and availability of services such as restaurants often makes the streets very active and feel alive. There are many people walking in the community and they are visible from the third floor. Many Montrealers will spend their evenings on the front porch watching their neighbours and cyclists go by. It is also common to stroll through the neighbourhood and meet a friend or neighbour to chat

Source: MTL Blog |

Because many people are on the street in the evening, there is an energy that is tangible. Many people are going to a cafe, park, or public space. There is an inviting feeling on the street-level. Jan Gehl theorized that cities of this density are more neighbourly because you can see facial features of those who pass by and connect with them. Any increase in building height will lose this key advantage.

- A History of Building and Maintaining Affordable Housing

Many Montrealers feel welcome in their cities because of the availability of affordable housing. The availability of greater affordable housing through the city allows people of diverse backgrounds and incomes to access public space and parks that are scattered throughout the city.

Research conducted by Anne-Marie Seguin and Annick Germain at the University of Toronto examined the City of Montreal during the 1990s, a period where the city was challenged with poverty, unemployment and increasing rates of immigration[1]. The researchers examined census tracts where 30-40% of the population was low income, but found that the neighborhoods maintained a social mix that was reflective of the greater Montreal Census Metropolitan Area; the census tracts studied were not dominated by groups of unemployed, uneducated, recently immigrated, or other disadvantaged groups. [2] The researchers pointed to strong governmental partnerships and initiatives to promote access to education, access to health resources, and the prevalence of strong initiatives to build affordable housing or renovate older housing stock.[3]

Coming back to the design of the rowhouses, from street-level there are no visible “poor” or “higher incomes” in row-houses because of the similarity in form and material. Any distinction between the rowhouses happened as a result of resident personalization rather than the developer or city guidelines. Unlike cities that promote basement suites or other “hidden” forms of density where the single family house remains supreme, the plex design is equal to everyone regardless if someone wishes to live at street level, second floor, or third.

Because neighbourhoods are designed similarly with row-houses or plexes, there are less rich enclaves within the city where people of a certain economic class are only welcomed to a public space or park, or not welcomed.

- Lack of towers in neighbourhoods and near transit

“Above the fifth floor, offices and housing should logically be the province of the air-traffic authorities. At any rate, they no longer belong in the city.”

” – Jan Gehl

Contrasting against Montreal’s livable density is a propensity of towers found in Vancouver or Toronto. Towers designed to “maximize” views lend themselves to just observing outside and to see far distances, not people. There is a clear disconnection from the ground level. Vancouver and the region specializes in these towers where residents are more apt to stay in their apartments, or amenity rooms while looking over far distances such as the north shore mountains rather than life on the street.

- A lack of backyards (and city requirements)

This might be the most controversial opinion offered in this essay, but it should be noted that the plexes and row-homes in Montreal have little or no amenity spaces such as rooftop pools, tennis courts, gyms, or even large backyards. These design elements that planners will agonize over and over-design, will add costs to a strata or rental rates that may be too much for an average to below average earner.

Rather, Montreal encourages use of public space by placing fountains, sprinklers, and picnic areas in each neighbourhood. As a result all residents of different backgrounds are able to access the shared spaces. An innovative step to create more place for people in Montreal was the launch of the “ruelle vertes,” or green alleys initiative which would took space from vehicles in rear lanes and converted them to green routes that are traffic calmed, or completely pedestrianized. The ruelle vertes often become playground for children, or places where neighbours can sit and have a shared meal.

Source: http://www.eco-quartiers.org/ruelle_verte |

- Flexibility from the city and the use of pop-up events

The city recognizes that there is an abundance of creative and cultural capital in the city. One way that the city promotes this capital is by permitting a wide variety of events in vacant industrial areas, parking lots, and parks. The city allows its residents to host temporary displays or concerts in parks that may only last a weekend, or the entire summer.

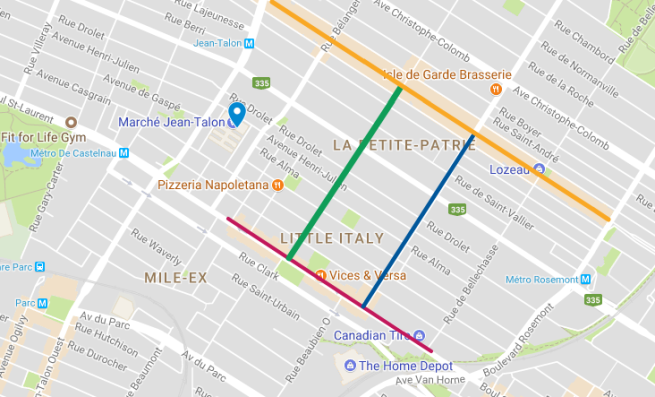

Two major pop-ups in the Mile-End neighbourhood this summer were the Aire-Commune event space, and the Marché des Possibles. In both cases, there existed vacant land that was to be transformed. Aire-Commune used a gravel lot near a railway to create a shared workspace for creatives during the day and event space at night. Supporting this initiative was the amount of office workers nearby, who would choose to come out and enjoy the sun while they worked or met clients during the day, then meeting friends after work.

Montreal also renewed a section of industrial waterfront to create a beach-like atmosphere in the middle of the city. The Pied Du Courant was a popular event space for the World Cup and throughout the summer as different musical acts played and people could have BBQ’s along the water.

Source: http://www.aupiedducourant.ca |

Marché des Possibles, on the other hand used a parking lot site and a small parklet to host weekend markets and concerts featuring local bands and DJs. An informal stage was set-up in the parklet and different themes were able to decorate the park, such as a Japanese theme.

The parking lot was taken over and used for food trucks where young people or families could buy dinner and enjoy it outside or have a beer. There were no onerous parking requirements or a roped-off zone where people could drink, rather people were able to wander around the parklet, or even head over to the nearby Aire-Commune.

Some conclusions..

Montreal has been able to successfully create and animate their public space by allowing people to feel welcome in all parts of the city. This has been no easy task, and has required planning efforts in all stages and sectors within the city. In order to allow multiple people to stay in the spaces, Montreal has committed to affordable housing in all parts of the city so there are no rich or poor enclaves or spaces. This is a commitment to the flexible and dense housing form found throughout the island of Montreal, the rowhouse. Strategically placed affordable housing initiatives using this housing form, as described by Anne-Marie Seguin have been important in fostering equity in the city.

Montreal also recognized that people have different incomes and expenses, so the city is designed in a way that people can vacation in their city and spend time in greenspace. The only way to vacation or enjoy the summer is not just loading up an SUV and heading to a large park outside of the city. The results have been excellent and the city feels lively.

Finally, the City has allowed flexibility in requirements to allow creativity and culture to flourish within the City. “No Fun City” rules have not been able to dominate the landscape and restrict citizens from enjoying themselves in the diverse and numerous pop-up events all over the city.

Cities across Canada can learn from Montreal if they wish to creative fun and inclusive cities for people.

Resources

Seguin, Anne-Marie, and Annick Germain. The Social Sustainability of Montreal: A Local or State Matter? The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change. University of Toronto.